A Capital Market's Perspective on Valuations

Time value of money, investing at its core, valuing bonds, and valuing equities

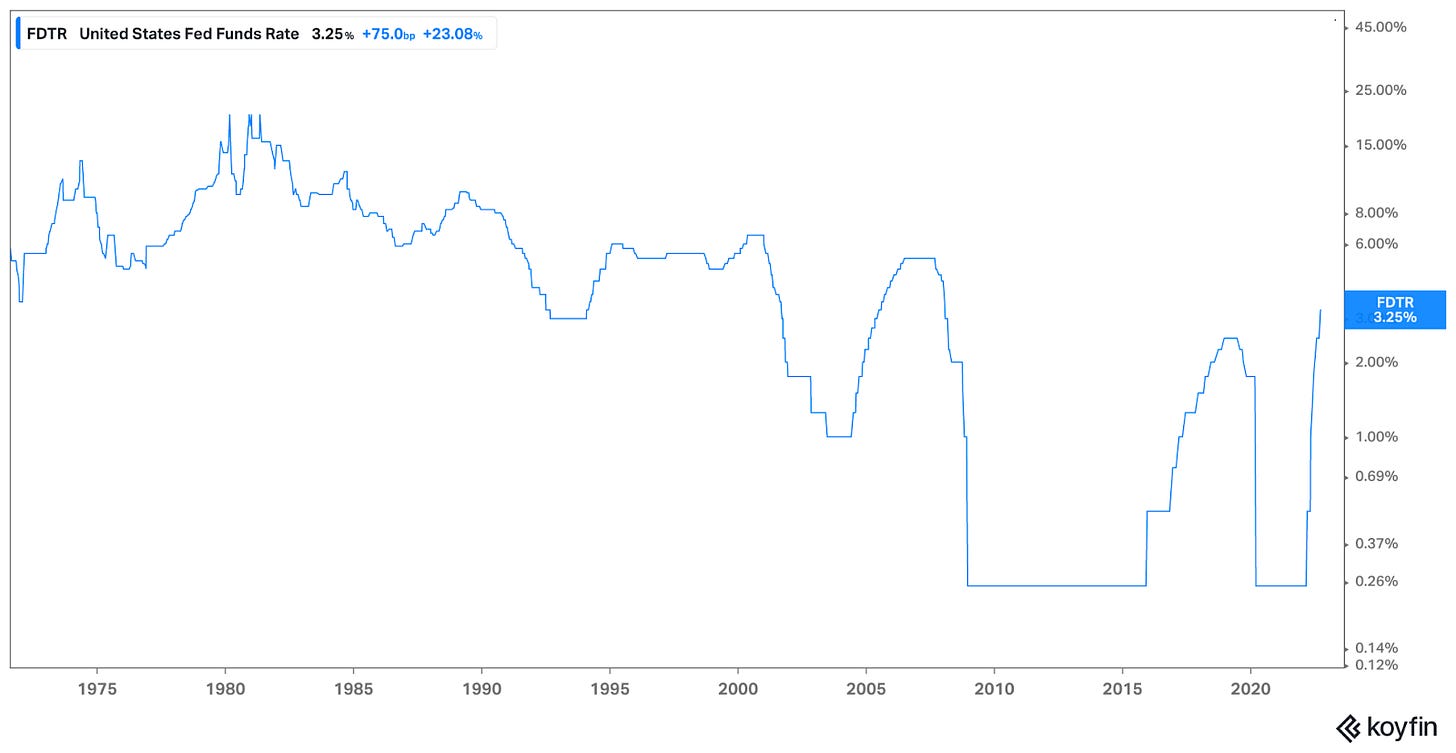

In an attempt to counteract inflation, the Fed has been raising interest rates at the fastest pace since 2000.

Markets have taken notice.

In 1970 Martin Zweig – finance professor, famed investor, and author of Winning on Wall Street – coined the phrase “Don’t fight the Fed” to explain the strong correlation between Federal Reserve’s actions and pressure on various asset classes.

This article seeks to build intuition of this phenomenon through conceptual understanding. For related explorations through academic and practical perspectives, see understanding intrinsic and relative valuation methods and the effect of interest rates on equity valuations.

Time Value of Money

First, we need to level-set on foundational concepts.

When the economy is in an inflationary environment (most of the time), money in the present is more valuable than money in the future. This is recognized through purchasing power.

Consider the following scenario:

You have $100 in your checking account.

Inflation is at 8%.

In year 0, you have $100 and you can purchase $100-worth of things. You can afford widget A.

In year 1, widget A costs $108. If you had kept your $100 in your checking account, you can no longer afford it. Your purchasing power would have declined. You still have $100, but widget A now costs $108.

Your $100 in year 1 can only afford things that cost $100 in year 1, which in year 0 would have cost $92.59.

Fast forward to year 3, widget A now costs $125.97. You still have only $100 in your checking account.

At this point, you can really only afford things that used to cost $79.38 in year 0, such as widget B. Widget B costs $100 in year 3.

The key takeaway is that, in an inflationary environment, where prices for things are going up, money in the present is more valuable than the equivalent nominal value of money in the future.

With that, we can move on to the next fundamental concept – why do people invest?

Investing at Its Core

What does it really mean to invest? Many people invest to have their money work for them and to have more money in the future.

At its core, investing can be thought of as the act of trading capital for cash flow. That is it.

If you have $1 million, you can either keep your $1 million dollars or invest that money in an asset that generates cash flow. If you could invest that at a 6% rate, you could “trade” your capital for $5,000/month.

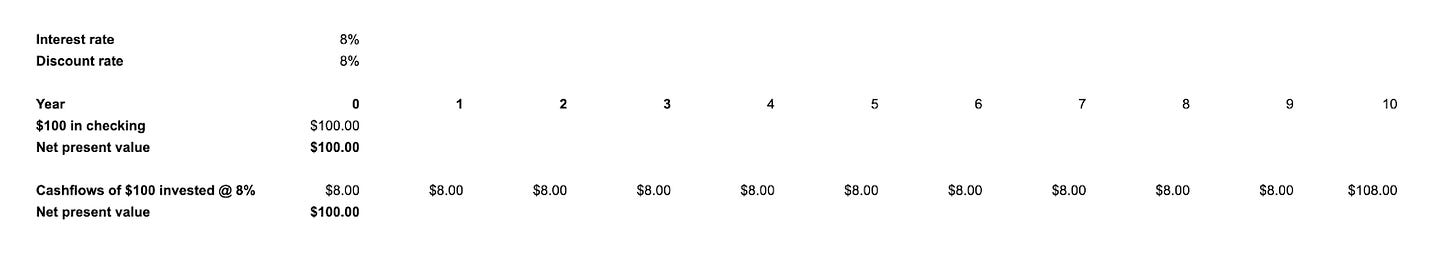

Consider the following conceptual example. You have $100 that you can either keep or invest at an 8% interest rate for 10 years. You can choose between capital or cash flow.

If you keep your $100 in your checking account, it is worth $100 in year 0.

If you invest your $100, over the 10 year period, you will have received payments every year plus a return of capital at the end.

Both scenarios are equivalent in terms of economic value.

In scenario 2, you receive much more than $100 in cash. But because those cash flows are spread out over many years in the future, they are worth less in year 0 dollars. Those future cash flows have to be “discounted” to today.

In this scenario, we “discounted” the cash flows at an 8% rate, equivalent to our interest rate.

The discount rate is an important, nuanced concept. It isn’t always equal to the interest rate or the rate of return. It seeks to answer the question “what expected return would I be satisfied with?”.

Given a particular expected return, you can derive a price you’d be willing to pay for the asset today.

If you want to match the rate of inflation, you can set my discount rate equal to inflation. If you have an alternative investment option that will yield you 10%, perhaps you set your discount rate to 10%. If an investment is particularly risky, you may require a much higher return and use a discount rate of 20-30%.

The discount rate should take into account certain external factors, such as alternative investment options, as well as internal factors, such as the risk inherent to the opportunity.

Discounting cash flows is one of the, if not the, core fundamental methods to value investments – simply figuring out how much future cash flows are worth today.

Valuing Bonds

“A bond is a debt security, similar to an IOU. Borrowers issue bonds to raise money from investors willing to lend them money for a certain amount of time.” - Investor.gov

Bonds are a great example of trading capital for cash flow. Bonds have a fixed duration and typically offer fixed cash flows throughout. The amounts and frequency of future cash flows are well known.

Treasuries are bonds issued by the US government. They are often considered a risk-free asset – it is generally accepted that the US government will make good on their payments.

For all other bonds, there is a chance those cash flows do not get paid out, if, for example, the issuing company were to go bankrupt. Because of this, you will want to incorporate an element of risk in your discount rate.

All of this should be taken into consideration when determining a discount rate.

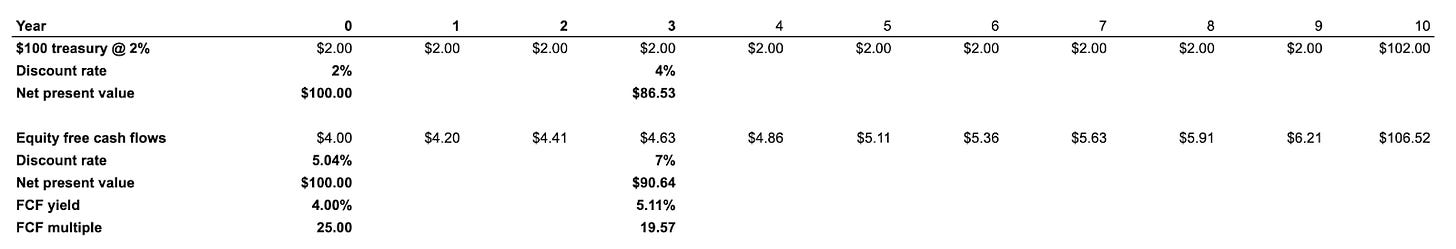

Consider the following example where treasuries yield 2% and corporate bonds yield 4%.

For treasuries, assuming they are risk-free, we can discount them at their 2% rate. We know we can expect the return that they offer.

Corporate bonds involve more risk than the treasuries. If the corporate bond yielded the same 2%, no one would invest in it and rather buy the treasuries instead. As investors, we require a premium for that risk. In the above example, the risk premium is an additional 2% for a total yield of 4%.

When holding bonds to maturity, there is only one decision to make when bonds are issued.

In the capital markets, however, bonds are quoted and traded daily.

While the coupon payments will not change, the value of the bonds can fluctuate depending on many factors.

Consider the risk-free rate rising to 4% in year 3 (i.e. all newly issued treasuries in year 3 yield 4%). This would have significant implications on the bonds issued in year 0.

In year 3, investors would have the choice between brand new treasuries or the existing treasuries. To get a higher yield, investors would begin selling the 2% treasuries and buying the 4% treasuries. This would happen until the point where the 2% treasuries are trading so cheaply that the future payments actually now return the same 4%.

The same phenomenon would happen with the corporate bonds. Investors would be able to choose. They could sell the risky 4% bonds for new risk-free 4% treasuries, or they could buy new risky corporate bonds for 6%. This would occur until the old corporate bonds trade at such a significant discount as to match the future rate of return.

In summary:

Bonds have fixed coupon payments, making it easier to know the future cash flows

The discount rate allows for subjectivity, since it depends on the risk involved (i.e. the risk of default will require a premium above the risk-free payment)

Markets will re-price assets depending on the other available options

For bonds, the cash flows are well known and the main variable in valuation is the discount rate.

Valuing Equities

The same fundamental ideas apply for equities – investors invest capital in equities in exchange for future cash flows. Those cash flows need to be discounted at an appropriate rate to determine the present day value.

Equities introduce a new critical variable, namely that future cash flows are unknown and uncertain.

There are different degrees of uncertainty in a company’s cash flows. For example, established compounders and other long standing companies may have more consistency and predictability in their business than newer companies that haven’t lived through various business cycles.

Even for the most stable companies, it is impossible to predict the cash flows perfectly. There are a confluence of unknown factors that could have implications on the business – changes in trends, management, supply chains, costs, competition, etc.

Additionally, there is no end date where all the remaining capital is returned. Companies continue to operate indefinitely until they are acquired or bankrupt, which again is unknown.

After determining some probable set of cash flows, which may be approximately correct but certainly not perfect, investors have to do the same of discounting them. Investors need to determine their willingness to pay and appropriate discount rate. Every investor will have a different perspective on the future cash flows, relevancy and duration of the company, and a distinct required rate of return for the risk they see.

To more easily compare yields, investors can look at a company’s free cash flow yield.

If a company is worth $100 (enterprise value = $100), and it generates $4 in free cash flow for the year, it would have a free cash flow yield of 4%. Alternatively, the inverse of this would be the EV/FCF multiple. This company would be valued at 25x its FCF.

The same can be done with the company’s earnings yield and P/E ratio. A company with a market cap of $100 and $4 in earnings would have an earnings yield of 4% and be trading at a P/E of 25x.

Although they are more complicated to value, equities are subject to the same changes in the macroeconomic environment as bonds. Equities and bonds are simply different ways to exchange capital for future cash flows.

Consider the following scenario:

A company that starts out with $4 in free cash flow in year 0

Free cash flow grows 5% every year

In year 10, the company is acquired and investors are cashed out

In year 0, when the $100 are invested, the discount rate for the equity is roughly 5%. This is a premium of 3% over treasuries. The FCF yield is 4% and the multiple is 25x.

In year 3, when the risk-free rate rises to 4%, the equities market will have to compensate.

In order to maintain the 3% risk premium, the equity will be sold down to the equilibrium point where the future cash flows now return at least 7%. The FCF yield is now 5.11% and the multiple has compressed to 19.57.

Even though the business itself has grown consistently over the years, and is forecasted to grow into the future, the business is now worth less in the capital markets.

This result is not because of anything the business did. Rather it is the result of the value the markets place on the future cash flows when compared to alternatives. Because the risk-free rate changed, all other investments adjusted accordingly.

In summary:

Equities have uncertain and unknown future cash flows, that allows for, or even requires, a significant level of subjectivity that is not present in the bond market

The discount rate also involves a lot more subjectivity and uncertainty, in part due to the unknown future

Markets will re-price assets depending on the other available options

When valuing equities, the future cash flows are unknown, adding another critical dimension on top of bonds.

Closing

Bond investors are often referred to as the “smart money”. In reality, there are fewer variables to consider, which makes it easier to focus on getting fewer things right. For the same reason, bonds are considered to be less risky when compared to equities. Risk and return are correlated over time.

Equities, due to the inherent uncertainty, require a higher return hurdle and require a higher discount rate. While returns will vary year to year, equities have consistently generated higher returns over time

Whether publicly traded or privately held, the value of every business is impacted by changes in the risk-free rate. Because the nominal amounts stay consistent and privately-held businesses are not constantly quoted, investors or owners of privately-held businesses likely feel less psychological impact. From a capital market perspective, a business is simply a vehicle that generates future cash flows which need to be discounted to today.

Returning to Zweig’s infamous phrase, “Don’t fight the Fed”, interest rates act as gravity on any asset class that seeks to generate future cash flow. As interest rates rise, those future cash flows are worth less because money is worth more today. The converse is also true. As interest rates subside, future cash flows become worth more today.

--

Torre Financial is an independent investment advisory firm focused on emerging and established compounders.

Federico Torre

Torre Financial

federico@torrefinancial.com

https://torrefinancial.com

Disclaimer: This post and the information presented are intended for informational purposes only. The views expressed herein are the author’s alone and do not constitute an offer to sell, or a recommendation to purchase, or a solicitation of an offer to buy, any security, nor a recommendation for any investment product or service. While certain information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, neither the author nor any of his employers or their affiliates have independently verified this information, and its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Accordingly, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to, and no reliance should be placed on, the fairness, accuracy, timeliness or completeness of this information. The author and all employers and their affiliated persons assume no liability for this information and no obligation to update the information or analysis contained herein in the future.